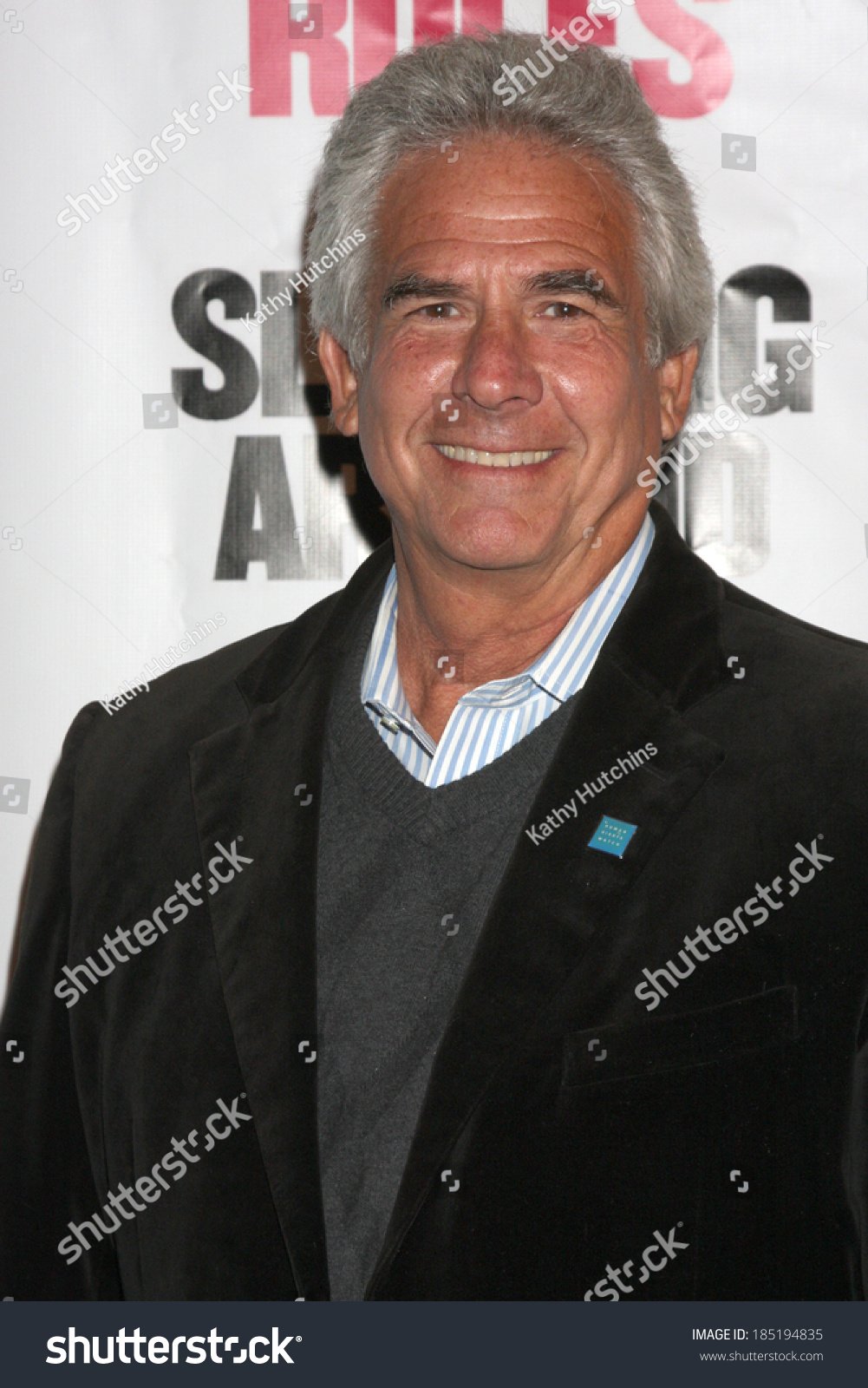

Larry Gilman's Impact on 60s/70s Rock Production Defined a Sound

The soundscape of 60s and 70s rock was a sprawling, rebellious, and relentlessly innovative frontier. It was a time when studio wizardry wasn't just about capturing a performance; it was about crafting an experience, building sonic worlds, and pushing the boundaries of what popular music could be. Amidst this whirlwind of creativity, a select few producers emerged as true architects of sound, shaping not just individual hits, but entire genres. Larry Gilman, with his distinctive touch, was undoubtedly one of these pivotal figures, leaving an indelible mark on an era that continues to resonate today.

Gilman's approach to production wasn't merely technical; it was an artistic philosophy that understood the raw energy of rock and rolled it into something polished yet powerful, commercial yet credible. His work embodied the spirit of experimentation and the burgeoning respect for the studio as an instrument in itself, helping define the very essence of what a "rock producer" could achieve.

At a Glance: Larry Gilman's Enduring Influence

- Pioneering Sonic Textures: Gilman pushed the envelope on how instruments and vocals could blend, creating dense, immersive soundscapes that became hallmarks of the era.

- Artist-Centric Approach: He fostered environments where musicians felt empowered to experiment, often extracting career-defining performances.

- Embracing Studio as Instrument: Gilman saw the recording studio not just as a capture device, but as a creative tool, leveraging early technological innovations for artistic effect.

- Bridging Genres: His work often blurred the lines between emerging rock styles, contributing to the diversity and evolution of both 60s beat and 70s progressive rock.

- Defining the Album Era: Understanding the shift from singles to cohesive LPs, Gilman championed the concept of the album as a unified artistic statement.

The Genesis of a Sound: Production in the Early Rock Era

Before the rock producer became a star in their own right, the role was often more utilitarian. But as the 1960s dawned, the landscape of popular music was rapidly changing, demanding a new breed of studio visionary. The early 60s saw the rise of intricate vocal groups and new rock-and-roll hybrids. Producers like Phil Spector, with his famed "Wall of Sound," weren't just recording; they were composing with sound, turning girl group tracks into "mini-dramas." Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys meticulously layered harmonies and Chuck Berry-inspired riffs, while Berry Gordy's Motown empire built a unique commercial sound from gospel roots, driven by producers like Smokey Robinson and the Holland-Dozier-Holland team.

This nascent period was characterized by a "creative technological DIY" spirit. Studios were becoming playgrounds for experimentation, and producers were approaching the commercial challenge as an artistic one. This was the vibrant, fertile ground where Larry Gilman began to forge his reputation. He wasn't content to simply record what an artist brought in; he sought to amplify their vision, often pushing them (and himself) into uncharted sonic territory.

Across the Atlantic, the British beat groups, like The Beatles, adopted a similar DIY ethos. They sharpened their attack, using group vocal harmonies decoratively and drawing inspiration from diverse American sources. British guitarists like Eric Clapton began shifting from simple rhythm to ornate lead playing, adding a new layer of complexity to rock arrangements. By the late 60s, British rock emphasized self-expression and original songwriting, moving beyond mere pop commercialism. This evolution provided a rich canvas for producers like Gilman, who understood that rock was rapidly becoming an art form demanding nuanced production.

Gilman's Sonic Architecture: Building Immersive Soundscapes

Larry Gilman carved out his niche by focusing on the texture and depth of sound. He was a master of layering, treating each instrument and vocal not just as individual elements, but as components of a larger, cohesive sonic tapestry. While Spector’s "Wall of Sound" was about immense density, Gilman’s approach was often more about clarity within complexity, allowing individual parts to breathe while contributing to an expansive whole.

Consider the burgeoning psychedelic movement of the mid-60s, epitomized by bands like The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane in San Francisco. As this sound became the soundtrack for the counter-culture, Gilman recognized the need for production that mirrored the expansive, often hazy, and richly textured experiences of the era. He wasn't afraid to experiment with reverb, delay, and early modulation effects, using them not as gimmicks, but as essential tools to convey emotion and atmosphere. His productions often felt widescreen, drawing the listener into an immersive sonic journey.

Much like how Pink Floyd and Cream set new standards for musical skill and technical imagination by the late 60s, Gilman championed recordings that felt technically innovative without sacrificing soul. He might spend hours meticulously placing microphones or experimenting with tape speeds to achieve a particular character for a drum sound, or he'd layer vocal harmonies until they shimmered with an otherworldly quality. This obsessive attention to detail, combined with an innate understanding of musicality, allowed him to create a distinct aural signature.

The Producer as Catalyst: Nurturing Artist Vision

Beyond the technical prowess, Gilman excelled at being an artist's producer. He understood that the best records emerged from a collaborative environment where trust was paramount. In an era when bands were increasingly expected to write their own songs, signifying self-expression over pop commercialism, Gilman was adept at helping artists translate their raw ideas into fully realized productions.

He had a reputation for getting the best out of musicians, whether it was through patient guidance, challenging them to push their own boundaries, or simply creating a relaxed atmosphere where creativity could flourish. This hands-on, deeply involved approach was crucial during a time when artists like Bob Dylan amplified their instruments and sharpened their beat, demonstrating that pop songs could offer profound social commentary. Gilman understood that this newfound depth required production that was equally thoughtful and expressive.

For instance, in the late 60s, as British rock groups further defined their music as art—with albums like The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band symbolizing the shift from pop to rock—Gilman was there to help artists articulate their artistic statements. He encouraged unconventional instrumentation, non-linear song structures, and conceptual album-making, aligning his studio work with the evolving artistic ambitions of the bands he produced. His studio became a sanctuary where musical ideas, no matter how avant-garde, could be explored and refined. To truly grasp the breadth of his influence, you'd want to Learn more about Larry Gilman and his unique methodologies.

From Singles to Albums: Defining the Rock LP

The 1970s began as the decade of the rock superstar, characterized by high album sales that gave musicians significant leverage over record companies. This shift from a singles-driven market to an album-oriented one was a critical development that Larry Gilman not only embraced but actively shaped. He understood that an album wasn't just a collection of songs; it was an extended narrative, a sonic journey with its own arc and flow.

Gilman's albums often displayed a deliberate sequencing, with tracks transitioning seamlessly or building thematic tension. He paid keen attention to the overall sonic cohesion of an LP, ensuring that even diverse songs felt like parts of a unified statement. This foresight was invaluable during a period where progressive rock bands like Yes, Genesis, and Pink Floyd were releasing complex, multi-movement works. Gilman's engineering background and his ear for musical drama made him the ideal collaborator for such ambitious projects. He'd consider the sonic spaces between tracks, the emotional resonance of an album's opening, and the lasting impact of its close, much like a film director crafting a cinematic experience.

This meticulous approach helped define the concept of "album-oriented rock" (AOR), which would become a dominant force on FM radio stations throughout the 70s. While Top 40 radio focused on individual hits, Gilman's work was often designed for the deep listen, rewarding repeated plays and revealing new layers with each hearing.

Navigating the Diverse Currents of the 70s: From Hard Rock to Glam

The 1970s were a kaleidoscope of evolving rock genres, and Larry Gilman proved to be remarkably versatile, adapting his production philosophy to suit the distinct needs of each new sound.

- Hard Rock & Heavy Metal: As psychedelic music evolved into the heavier sounds of Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, and The Who, Gilman understood the necessity of raw power and monumental drum sounds. He experimented with close-miking techniques and aggressive EQ to give instruments a visceral presence, ensuring that the sheer force of these bands translated effectively onto vinyl. His productions emphasized clarity in distortion, allowing intricate riffs to cut through the sonic aggression.

- Glam Rock's Theatricality: When Glam/Glitter rock burst onto the scene with artists like David Bowie, T.Rex, and The Sweet, Gilman recognized the theatricality and flamboyant aesthetic of the genre. His productions for glam artists often featured brighter, more polished sounds, with prominent, often layered, vocals and arrangements that hinted at grandeur and spectacle. He embraced the playful artifice, using studio effects to enhance the larger-than-life personas of these acts.

- Singer/Songwriter Intimacy: Amidst the stadium rock and glitter, the early 70s also saw the flourishing of singer-songwriters like James Taylor, Carole King, and Joni Mitchell. For these artists, Gilman's touch was subtler, focusing on intimacy and emotional directness. He understood how to create a transparent production that highlighted the vulnerability of a voice and the delicate nuance of an acoustic guitar or piano, allowing the lyrics and melody to take center stage without distraction. His skill lay in knowing when to enhance and when to simply capture, making the studio feel like an extension of a living room performance.

- Progressive Rock's Complexity: Gilman's ability to manage complex arrangements, intricate time signatures, and multi-layered instrumentation made him a natural fit for progressive rock bands. He was able to wrangle ambitious compositions into cohesive sonic experiences, ensuring that the virtuosity of musicianship was never lost in the grandeur of the sound. He facilitated the seamless integration of synthesizers, orchestral elements, and experimental textures, which were hallmarks of groups like Emerson, Lake and Palmer or Rush.

Throughout these stylistic shifts, Gilman maintained his commitment to pushing sonic boundaries while always serving the artist's vision. His productions were never generic; they carried a distinct quality that spoke to the spirit of innovation defining rock music in the 60s and 70s.

The DIY Ethos and Technological Embrace

The 60s and 70s were a period of rapid technological advancement in recording studios. From the adoption of multi-track recorders (8-track, 16-track, then 24-track) to new synthesizers and outboard gear, producers had an expanding palette of tools. Larry Gilman was an early adopter and experimenter, embodying the "creative technological DIY" spirit identified with pioneers like Spector and Wilson.

He understood the potential of each new piece of equipment not just for novelty, but for artistic expression. He experimented with phasing, flanging, and tape loops, often building custom signal chains or modifying existing gear to achieve unique sounds. This hands-on approach to technology meant his productions often had a distinct sonic fingerprint that was difficult for others to replicate.

For instance, as car stereos became common and features like FM stereo, 8-Track, and cassette tapes proliferated, Gilman keenly observed how his music would be consumed. He understood the need for mixes that sounded great across different playback systems, from high-fidelity home stereos to tinny car speakers. This commercial awareness, coupled with his artistic drive, made his records not only innovative but also broadly appealing. The way he meticulously crafted sounds ensured that, regardless of the listening environment, the essence of the track remained intact.

Gilman's Legacy: A Blueprint for Modern Producers

Larry Gilman's impact on 60s and 70s rock production extended far beyond the specific records he produced. His real legacy lies in the approach he popularized: treating the studio as a creative crucible, empowering artists, and relentlessly pursuing sonic excellence. He helped establish the role of the producer as an indispensable creative partner, a figure whose vision could elevate a band's raw talent into something truly iconic.

In an era that witnessed the rise of arena rock and the industry's first major crisis in the late 70s (due to economic recession and new leisure activities), Gilman's focus on quality and artistic integrity was a steadfast anchor. While disco dominated singles charts and punk rock emerged as a raw, minimalist reaction to arena rock excess, Gilman's work consistently championed rock's diverse and evolving forms.

His methods, centered on detail, atmosphere, and artistic collaboration, provided a blueprint that continues to inspire modern producers. When you listen to the layered textures of contemporary indie rock, the meticulous sound design of electronic music, or the emotional resonance of a well-produced singer-songwriter album, you can hear echoes of the foundational principles that Larry Gilman helped establish.

He was a master at navigating the complex interplay between technology, artistry, and commerce, ensuring that the powerful, rebellious spirit of rock music was always captured with maximum impact. His influence demonstrates how the right producer can not only capture a moment in time but also define its enduring sound for generations to come.